The Forecast Is Clear: Clouds on E-Paper, Powered by the Cloud

I’ve noticed that many shops are increasingly using e-paper displays. They’re impressive: high contrast, no backlight, and no visible cables. Unlike most electronics, these displays are seamlessly integrated and feel very natural. This got me wondering: is it possible to use such a display for a pet project? I want to experiment with this technology myself.

(source)

My main goal in this project is to understand the hardware and its capabilities. Here, I'll be using an e-paper display to show the current weather, but at its core, I’m simply feeding data from a website to the display. While it sounds straightforward, it actually requires three layers of software to pull off. Still, it’s a fun challenge and a great opportunity to work with both embedded hardware and Cloudflare Workers.

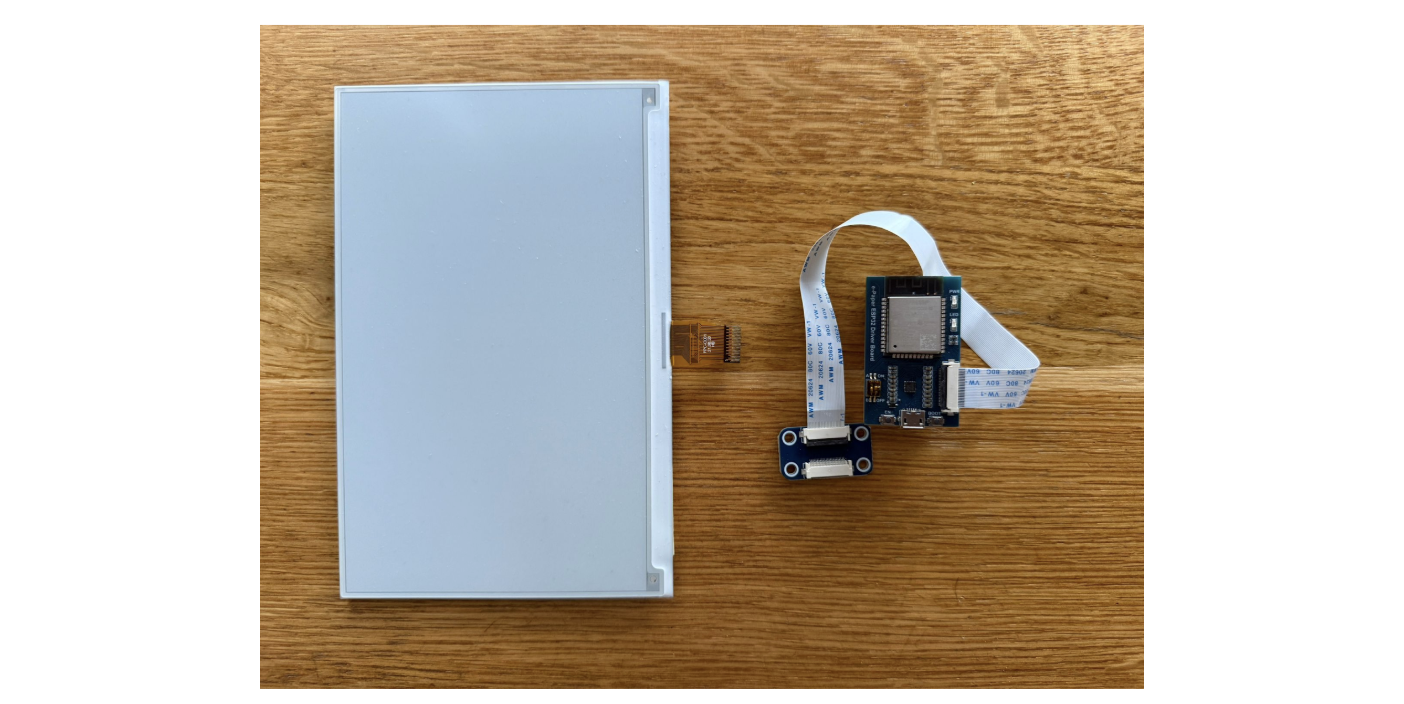

For this project, I'm using components from Waveshare. They offer a variety of e-paper displays, ranging from credit card-sized to A4-sized models. I chose the 7.5-inch, two-color "e-Paper (G)" display. For the controller, I'm using a Waveshare ESP32-based universal board. With just these two components — a display and a controller — I was ready to get started.

When the components arrived, I carefully connected the display’s ribbon cable to the ESP32 board. Even though this step isn’t documented anywhere, it was simple and almost impossible to get wrong. Best of all, no soldering was needed!

That’s pretty much it for the hardware setup! I’m keeping the device powered with a 5V supply through a micro-USB connection.

(source)

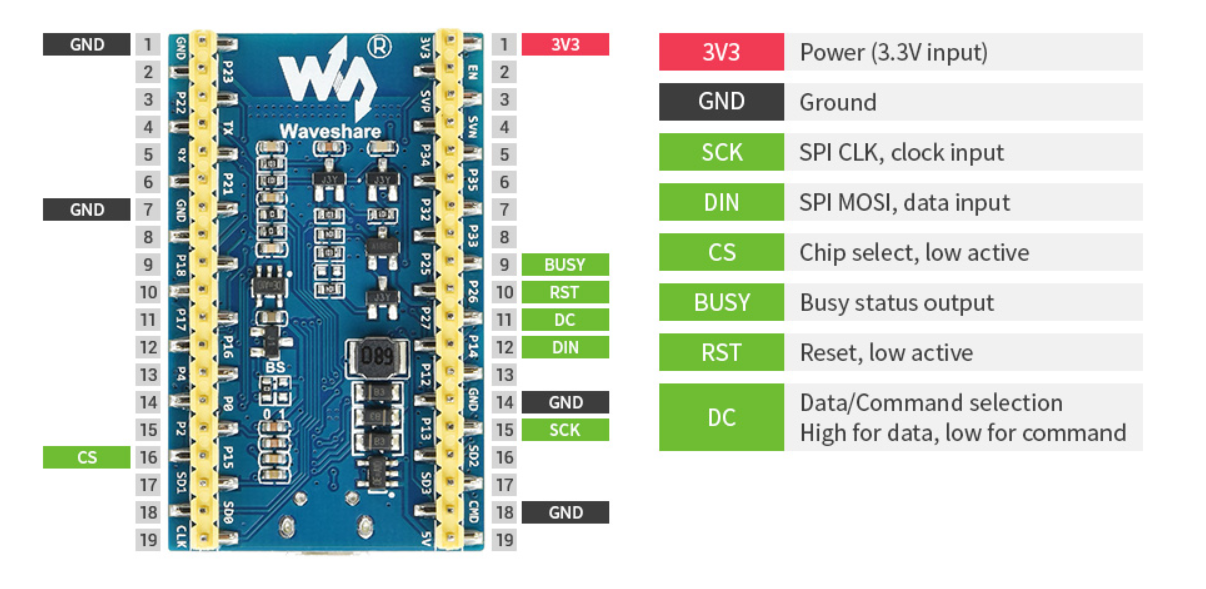

This was my first time working with the ESP32 CPU family, and I’m really impressed. It’s a system-on-chip controller with built-in Bluetooth and Wi-Fi. It’s relatively fast, very power-efficient, and quite popular in DSP (digital signal processing) applications. For example, your audio device might be powered by a CPU like this. Interestingly, the newer models have switched to the RISC-V instruction set.

For our purposes, we’ll only scratch the surface of what the ESP32 is capable of. The chip is straightforward to work with, thanks to the familiar Arduino environment. A great starting point is the demo provided by Waveshare. It sets up a web page where you can easily upload a custom image to the display.

To run the demo you need to:

Install the Arduino IDE.

Fix permissions of the

/dev/ACM0device.Install "Additional Boards Manager URL" as per the instructions, and install the "esp32 by expressif" bundle.

Open the "Loader_esp32wf" example downloaded from waveshare.

Change the Wi-Fi name, password and IP address in the Arduino IDE

srvr.htab.

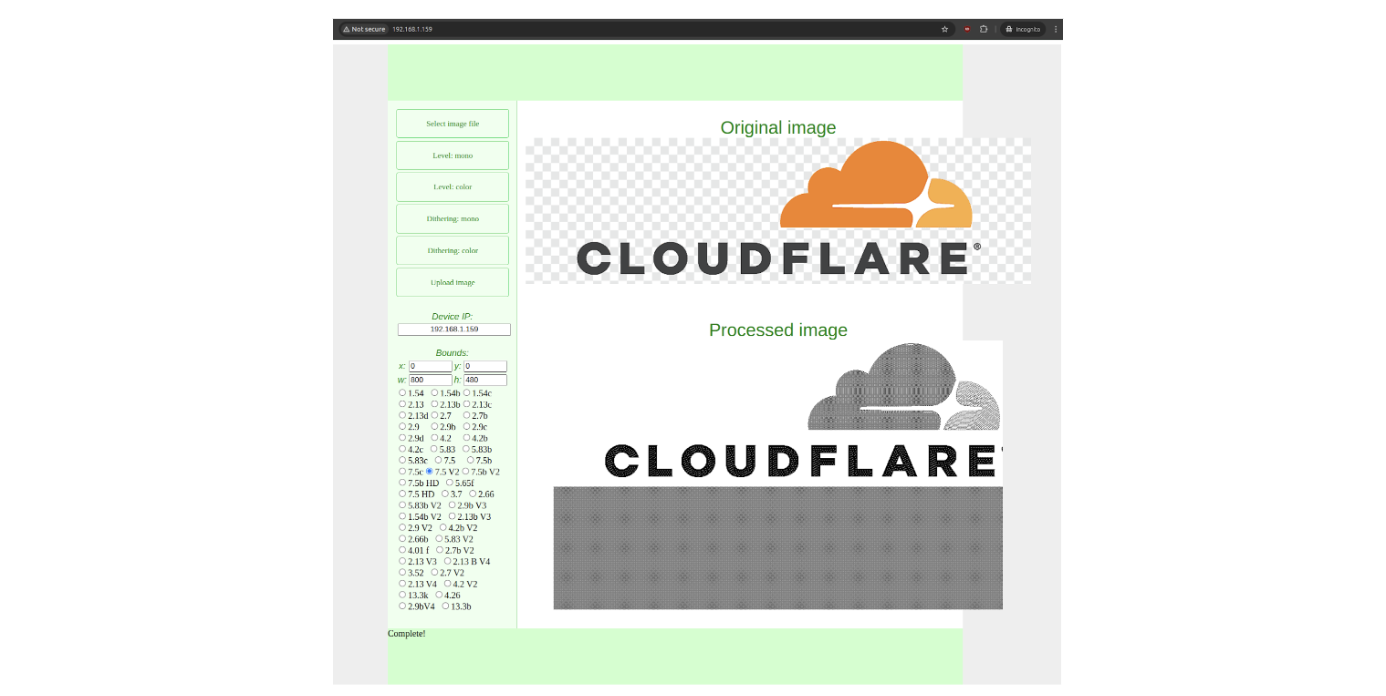

Once everything is set up, you should be able to connect to the ESP32’s IP address and use the simple web interface to upload an image to the display.

With a simple click of the "Upload Image" button, the magic happens: the e-paper display comes to life, showcasing the uploaded image.

With the demo up and running, we can move on to the next step: figuring out how to render a web page on the e-paper display.

The ESP32 comes with some limitations. It has 520 KiB of RAM, 4 MiB of flash, and a 240 MHz clock speed. While this is fine for tasks like connecting to Wi-Fi or fetching a simple URL, it’s not powerful enough for more demanding tasks, such as parsing JSON or rendering an entire web page.

There are basic Arduino libraries for handling bitmaps, which can draw rectangles and render simple fonts, but manually managing layout doesn't sound appealing to me. A better approach is to play to the ESP32’s strengths — fetching and displaying bitmaps — and delegate the more complex task of HTML rendering to a more powerful server.

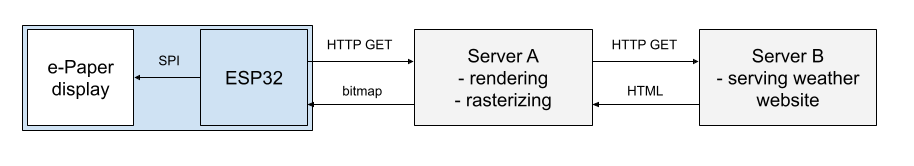

Let’s break the problem into three layers:

ESP32 (Display Layer): The ESP32 will periodically, say every minute, fetch a pre-rendered bitmap from the server and display it on the e-paper screen. This keeps the ESP32's tasks lightweight and manageable.

Server A (Rendering Layer): This server will fetch the desired website, render it, and rasterize it into a bitmap format. Its job is to prepare a bitmap that the ESP32 can handle without additional processing.

Server B (Content Layer): This server hosts the actual website with the HTML and CSS content. In this case, it will provide the local weather data in a styled format, ready to be fetched and rendered by Server A.

The ESP32 provides some great higher-level libraries to simplify development. For this project, we’ll need three key components:

Wi-Fi Arduino Library: To connect the ESP32 to a Wi-Fi network.

HTTP Arduino Library: To handle HTTP requests and fetch the rendered bitmap from the server.

EPD (e-Paper Display) Driver: To control the e-paper display and render the fetched bitmap.

These libraries make it much easier to implement the required functionality without dealing with low-level details.

Here's my ESP32 Arduino project code. It's actually pretty straightforward:

First, it connects to Wi-Fi

Then, it fetches a rendered bitmap from an HTTP endpoint

Then it pushes it to the e-paper display if needed

Waits a minute

And repeats the whole process forever

E-paper displays typically start to degrade after about one million refresh cycles. To preserve the display's lifespan, I’m being extra careful to avoid unnecessary refreshes.

Now for the exciting part! We need an online service that can fetch a website, render it, rasterize it to fit our small monochromatic display, and return it as a display-sized binary blob. Initially, I considered using headless Chrome paired with an ImageMagick script, but then I discovered Cloudflare’s Browser Rendering API, which fits our needs perfectly.

This API can be used quite trivially and nicely fits our needs. Here's the typescript worker code, and there are two particularly interesting parts: handling a remote browser and dithering.

First, see how easy it is to render a website as a PNG using Browser Rendering:

if (!browser) {

browser = await puppeteer.launch(env.MYBROWSER, { keep_alive: 600000 });

launched = true;

}

sessionId = browser.sessionId();

const page = await browser.newPage();

await page.setViewport({

width: 480,

height: 800,

deviceScaleFactor: 1,

})

await page.goto(url);

img = (await page.screenshot()) as Buffer;

I’m genuinely surprised at how practical and effective this approach is. While the remote browser startup isn’t exactly fast — it can take a few seconds to generate the screenshot — it’s not an issue for my use case. The delay is perfectly acceptable, especially considering how much work is offloaded to the cloud.

Dithering

To prepare the bitmap for the ESP32, we need to decode the PNG, reduce the color palette to monochromatic, and apply dithering. Here's the dithering code:

function ditherTwoBits(px: Buffer,

width: number,

height: number

): Buffer {

px = new Float32Array(px);

for (let y = 0; y < height; y++) {

for (let x = 0; x < width; x++) {

const old_pixel = px[y * width + x];

const new_pixel = old_pixel > 128 ? 0xff : 0x00;

const quant_error = (old_pixel - new_pixel) / 16.0;

px[(y + 0) * width + (x + 0)] = new_pixel;

px[(y + 0) * width + (x + 1)] += quant_error * 7.;

px[(y + 1) * width + (x - 1)] += quant_error * 3.;

px[(y + 1) * width + (x + 0)] += quant_error * 5.;

px[(y + 1) * width + (x + 1)] += quant_error * 1.;

}

}

return Buffer.from(Uint8ClampedArray.from(px));

}

This was my first time experimenting with dithering, and it’s been a lot of fun! I was surprised by how straightforward the process is and that it’s fully deterministic. Now that I understand the details of the algorithm, I can’t help but notice its subtle side effects everywhere — in printed materials, on screens, and even in design choices around me. It’s fascinating how something so simple has such a broad impact!

To deploy this code as a Cloudflare Worker, you only need to install the required dependencies, configure the wrangler.toml file, and publish the code. Here’s a step-by-step guide:

sudo apt install npm

cd worker-render-raster

npm install wrangler

npm install @cloudflare/puppeteer --save-dev

npm install fast-png --save-dev

npx wrangler kv:namespace create KV

npx wrangler kv:namespace create KV --previewWith this out of the way, you can run the code:

2025-01-e-paper/worker-render-raster$ npx wrangler dev --remote

⛅️ wrangler 3.99.0

Your worker has access to the following bindings:

- KV Namespaces:

- KV: XXX

- Browser:

- Name: BROWSER

[wrangler:inf] Ready on http://localhost:46131

⎔ Starting remote preview…

Total Upload: 755.39 KiB / gzip: 149.05 KiB

╭─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╮

│ [b] open a browser, [d] open devtools, [l] turn on local mode, [c] clear console, [x] to exit │

╰─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────╯

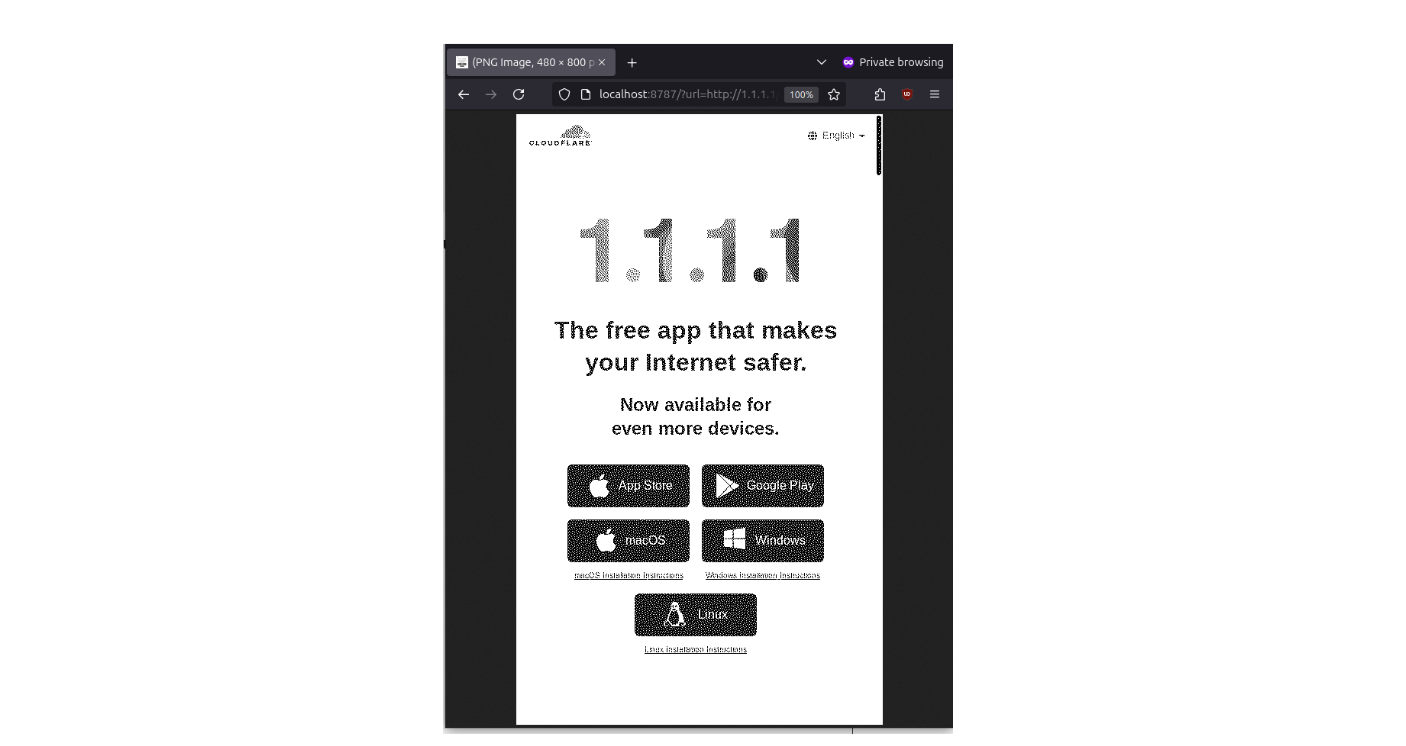

With everything set up, you can now open a browser and see a rendered and rasterized version of a website, processed through your Cloudflare Worker! For example, here’s how the 1.1.1.1 page looks in a 800x480 monochromatic resolution, complete with dithering:

This demonstrates how effectively the Worker can handle rendering, rasterizing, and adapting web content for an e-paper display. It’s quite satisfying to see the pipeline in action.

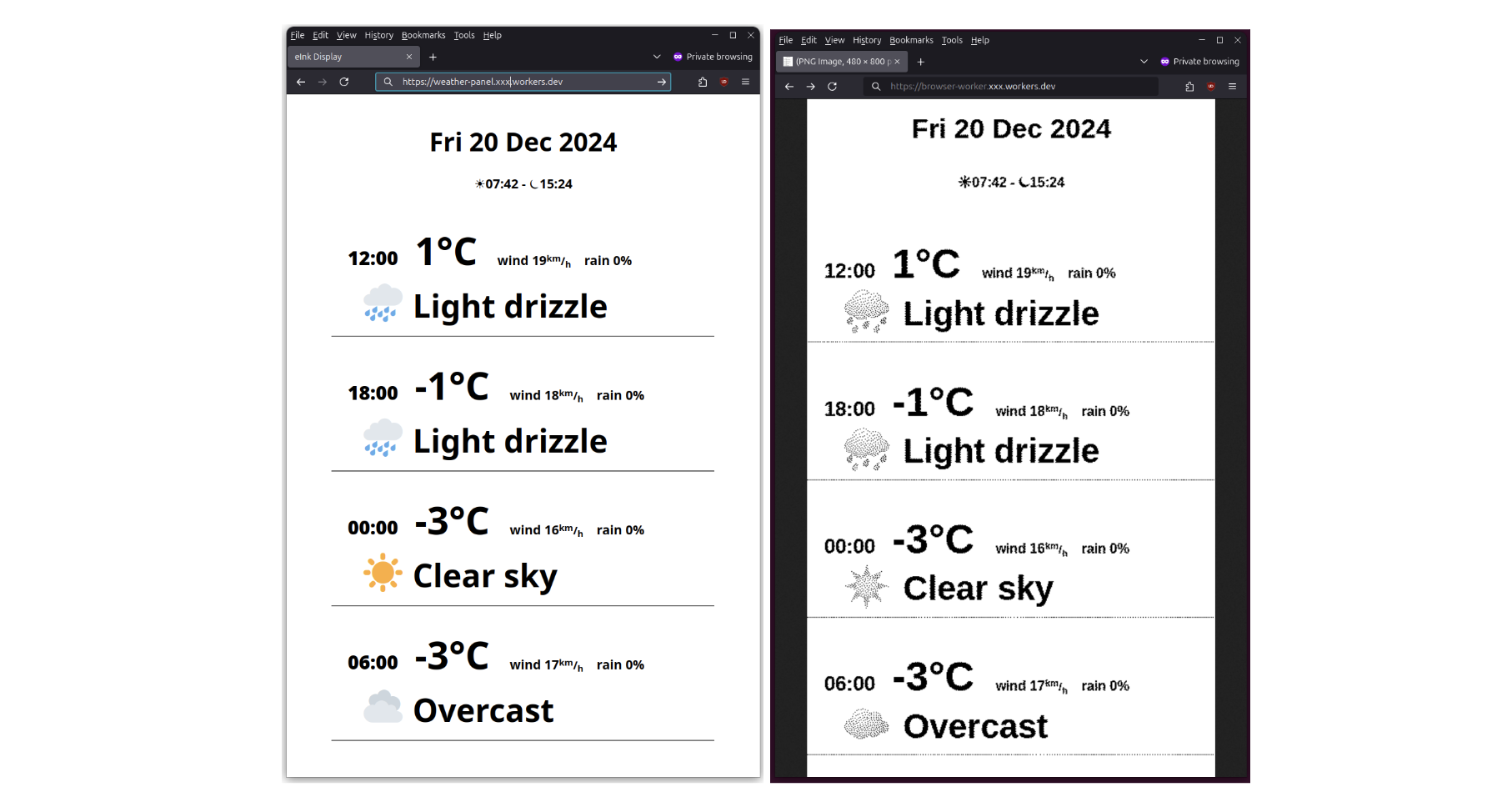

To create the weather panel, I designed a simple HTML and CSS page and published it as another Cloudflare Worker. This time, I used Python in Cloudflare Workers because it felt more straightforward, especially since the site needs to query an external weather API. The simplicity of the code was surprising and made the process smooth.

async def on_fetch(request, env):

cached = await env.KV.get("weather")

if cached:

cached = json.loads(cached)

else:

u = "https://api.open-meteo.com/..."

a = await fetch(u)

result = await a.text()

cached = json.loads(result)

await env.KV.put("weather", json.dumps(cached))

return Response.new(render(...), headers=[('content-type', 'text/html')])Here’s how it appears in a normal browser compared to the rendered and rasterized version by our worker:

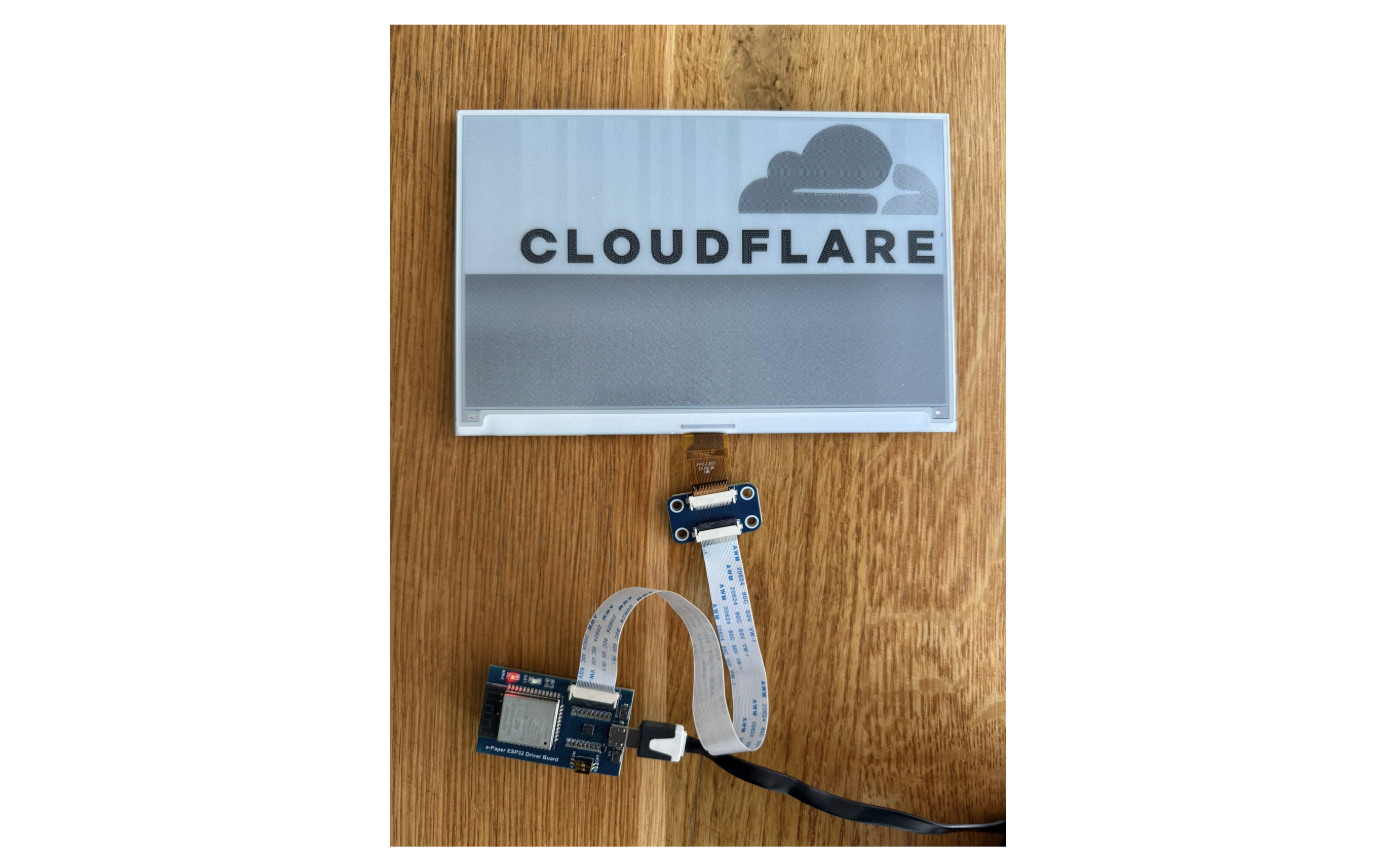

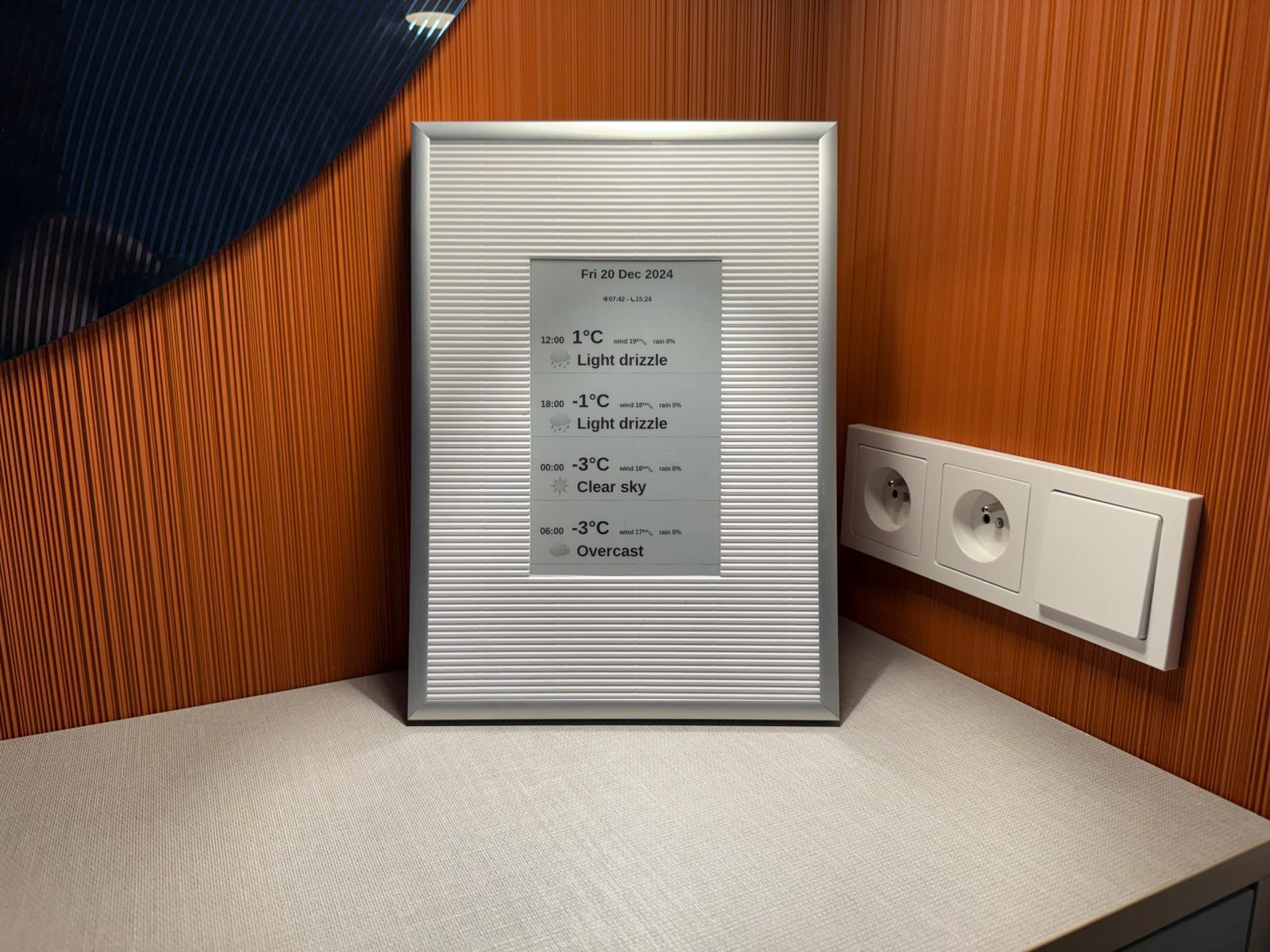

Finally, the display deserves a proper frame. Here’s the finished version:

I started this project wanting to experiment with an e-paper display hardware, but I ended up spending most of my time writing software—and it turned out to be surprisingly enjoyable across all layers:

ESP32: The CPU is fantastic. Programming it is straightforward, thanks to powerful built-in libraries that simplify development.

Cloudflare Worker Browser Rendering: This is an underrated but incredibly powerful technology. It made implementing features like the Floyd–Steinberg dithering algorithm surprisingly easy.

Cloudflare Worker Python: Although still in beta, it worked flawlessly for my needs and was a great fit for handling API requests and serving dynamic content.

It’s remarkable how much you can achieve with relatively inexpensive hardware and free Cloudflare services.